The era of incomprehensible medical scribbles may finally be drawing to a close in India, following a landmark judgment by the Punjab and Haryana High Court that has unequivocally linked a legible medical prescription to a patient's Fundamental Right to Health under Article 21 of the Constitution. The ruling, delivered by Justice Jasgurpreet Singh Puri, underscores a crucial shift from accepting a doctor’s poor handwriting as a common practice to recognizing it as a serious barrier to patient safety and information access.

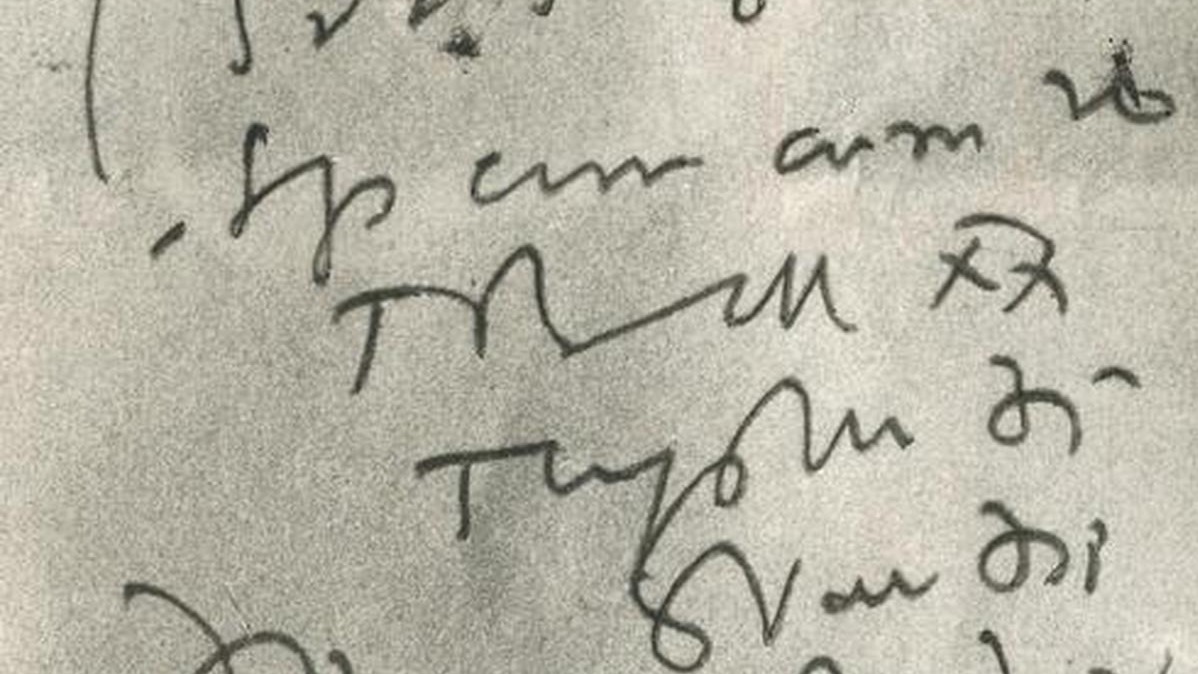

The genesis of this judicial intervention was remarkably coincidental. While hearing an anticipatory bail plea in a criminal case involving allegations of forgery and sexual exploitation, the court was "shook to its conscience" when the medico-legal report (MLR) presented as evidence was "not even a word or a letter legible." This baffling encounter with an unreadable medical document prompted the court to take suo motu cognizance of the issue, expanding the case far beyond the initial bail application to address a systemic problem plaguing the entire healthcare and legal ecosystem.

The core of the judgment is the forceful assertion that the Right to Life and Personal Liberty guaranteed by Article 21 encompasses the Right to Health, and this right, in turn, includes the Right to Know one's legible medical prescription, diagnosis, and treatment. The court highlighted the alarming risks associated with illegible prescriptions, noting that ambiguity and misinterpretation can lead to medication errors, incorrect dosages, or wrong treatments, all of which carry the potential for severe, even fatal, consequences for the patient. Furthermore, it noted that poor handwriting hinders a patient's ability to cross check information online or seek second opinions, thereby diminishing patient autonomy and limiting the benefits of modern digital health technologies, including Artificial Intelligence.

To combat this entrenched problem, the High Court issued a set of far reaching directives to the State governments of Punjab, Haryana, and the Union Territory of Chandigarh, as well as the National Medical Commission (NMC). Until a complete transition to computerized or typed prescriptions is achieved, all handwritten prescriptions and diagnoses by doctors must be written legibly and preferably in capital letters. The court also set a stringent two year timeline for the states to formulate and implement a comprehensive policy for the complete digitalization of prescriptions, with due consideration for providing financial assistance to clinical establishments if required. Crucially, the court directed the NMC to ensure that the importance of clear and legible handwriting is introduced and inculcated as a mandatory part of the curriculum in all medical colleges across India, stressing the need to train future doctors for a digital future while protecting the fundamental rights of the populace. This order firmly places the onus on the medical profession and governing bodies to prioritize clarity and patient safety, ensuring that a simple prescription does not become a matter of life or death.